Introduction

Project scheduling presents a fundamental challenge: given a set of tasks with varying durations, dependencies, and resource requirements, how can we predict when each task will complete? Traditional approaches often rely on static calculations that assume perfect conditions. The scheduler described in this article takes a different approach by simulating the actual flow of work through a team, day by day, accounting for the realities of team capacity, holidays, skills, and dependencies.

This article explains the scheduling approach used in the project simulation tool I wrote. The scheduler models how work items move through states, from backlog to in-progress to completed, while respecting constraints that exist in real project environments.

Design philosophy: simulation over optimization

“Remember that all models are wrong; the practical question is how wrong they have to be to not be useful.” (George E. P. Box)

The scheduler deliberately avoids attempting to find an optimal allocation of resources. An optimization approach would evaluate all possible sequences of task assignments to identify the execution path that minimizes total project duration or maximizes resource utilization. While mathematically elegant, this approach has limited practical value for software project scheduling.

Software projects operate in environments of constant change. Scope evolves as stakeholders refine requirements or respond to market conditions. Unanticipated technical issues emerge during implementation, sometimes requiring significant rework or architectural changes. Team availability shifts due to external requests, organizational changes, illness, or attrition. Dependencies on external teams or systems introduce delays outside the project’s control.

Given this reality, an “optimal” schedule computed at the start of a project would quickly diverge from actual execution. The computational cost of finding such a schedule, which grows exponentially with project size, yields diminishing returns when the underlying assumptions change frequently.

Instead, the scheduler relies on heuristics to produce a highly probable simulation of future activities. It models how work would flow through the team under current assumptions, applying reasonable rules for task selection and assignment. The result is not a guarantee but a forecast, useful for identifying potential bottlenecks, estimating delivery dates, and understanding resource utilization patterns.

This heuristic approach offers several advantages. It runs quickly enough to regenerate schedules as conditions change. It produces intuitive results that stakeholders can understand and question. It degrades gracefully when inputs are imprecise, since small errors in effort estimates produce proportionally small errors in predicted dates rather than cascading failures.

The scheduler treats the schedule as a living document, expected to be regenerated regularly as the project evolves, rather than a fixed plan computed once and followed rigidly.

The problem domain

Before examining the solution, let’s consider what makes project scheduling difficult. Team members have varying availability due to holidays, time-off, and part-time allocations. Tasks depend on other tasks, creating ordering constraints. Team members possess different skills and project access permissions. Work-in-progress must be limited to prevent context-switching overhead. Deadlines create urgency that affects prioritization. Parent tasks derive their schedules from their children.

A scheduling algorithm must account for all these factors while producing realistic completion date predictions.

Core concepts

Issue classification

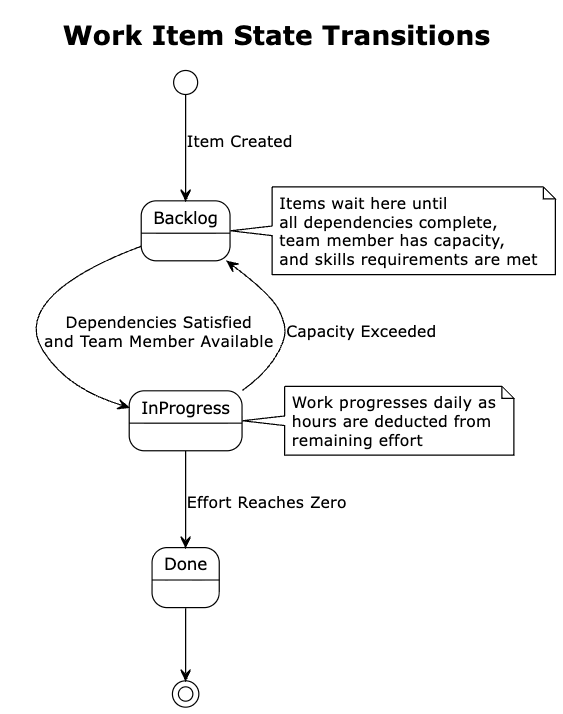

The scheduler categorizes work items into three primary states: Done items are completed with fixed historical dates; in-progress items are currently being worked on; backlog items are waiting to be started.

Additionally, items are classified as either leaf items, which are actual work units without children, or non-leaf items, which are containers that group related work (e.g. a Story containing multiple Tasks). The scheduler operates primarily on leaf items, then derives parent schedules from their children.

Team capacity model

The scheduler maintains a model of team capacity that tracks available working hours per team member per day, skills and project access permissions for each team member, maximum concurrent work items per developer, and holidays and time-off periods by geographic location.

This model allows the scheduler to answer questions like “How many hours can team member X work on day Y?” while accounting for weekends, holidays, and planned absences.

The simulation algorithm

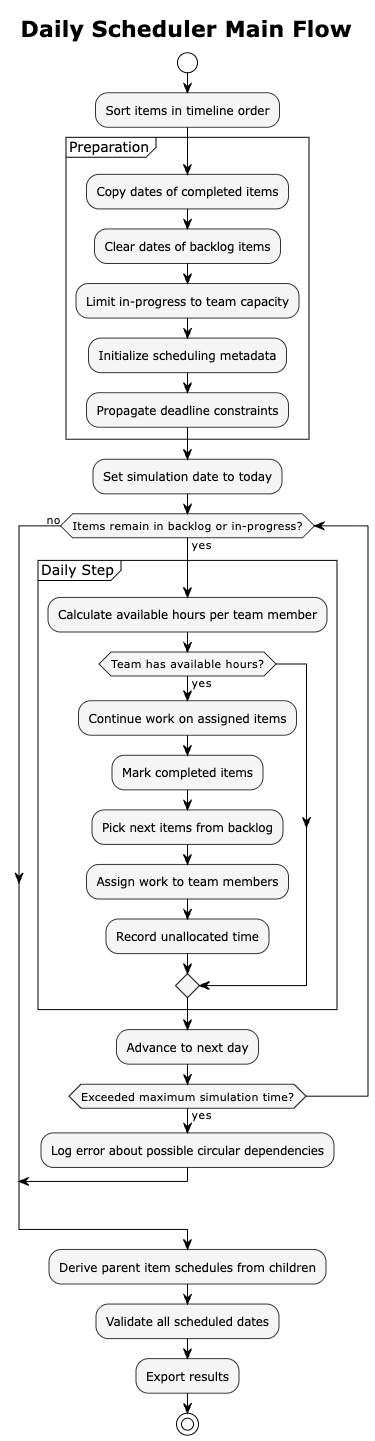

The scheduler uses a discrete-event simulation that advances through time one day at a time. Each simulated day follows a consistent processing sequence.

Preparation phase

Before simulation begins, the scheduler prepares the data through several steps.

First, it sorts all items in the order they would appear in a project timeline. It then preserves the dates of completed items, treating them as historical data that should not change. Next, it clears scheduled dates for backlog items since these will be computed during simulation. The scheduler limits in-progress items to team capacity, moving any excess to the backlog. It initializes scheduling metadata for all items and propagates deadline constraints from parent items to children.

The daily processing cycle

The scheduler awakens each simulated morning and surveys the landscape of work. Its first task is to understand what resources are available: it queries the team model to determine how many hours each team member can contribute today. Some team members may be on holiday, others working reduced hours, and weekends yield no productive time at all. If the entire team is unavailable, perhaps due to a national holiday, the scheduler simply advances to the next day without further action.

With available hours established, the scheduler turns its attention to work already in flight. Each team member continues laboring on their assigned items. The scheduler deducts hours from each item’s remaining effort, tracking progress as the day’s work accumulates. When a team member’s available hours for the day are exhausted, they stop working. When an item’s remaining effort reaches zero, it transitions to the completed state, and the scheduler records its completion date.

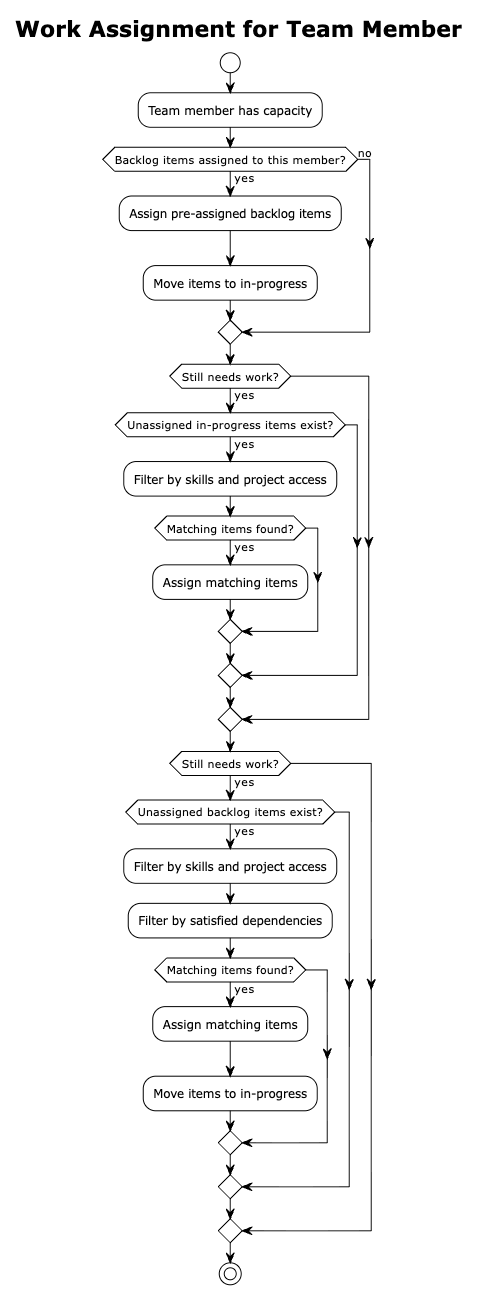

The completion of items creates capacity. Team members who finish their work, or who started the day with room in their queue, now need new assignments. The scheduler consults the issue picker, which examines the backlog and returns items ready for work. An item is ready only if all its dependencies are satisfied and its planned start date has arrived.

Assignment follows a deliberate sequence. The scheduler first looks for backlog items already assigned to each team member, respecting prior allocation decisions. If a team member still has capacity, the scheduler searches for unassigned items already in progress that the team member could help with. Finally, it considers unassigned backlog items. At each step, the scheduler verifies that the team member possesses the required skills and has access to the relevant project before making an assignment.

Not all capacity finds a home. Some team members may have hours available but no items they can work on. Perhaps all remaining items require skills they lack, or dependencies block every candidate. The scheduler records this unallocated time, providing visibility into capacity that went unused.

With the day’s work complete, the scheduler advances the calendar by one day and begins the cycle anew. This continues until the backlog empties and all in-progress items reach completion, or until the simulation reaches its maximum duration, a safeguard against circular dependencies that would otherwise cause the simulation to run indefinitely.

Dependency resolution

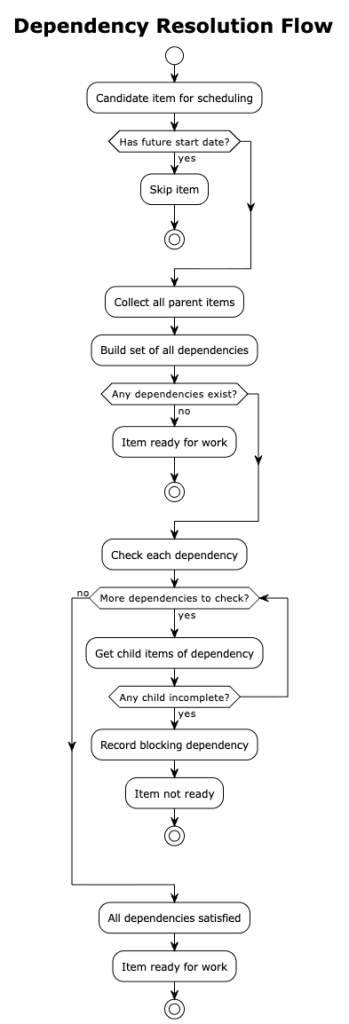

Dependencies create ordering constraints between items. An item cannot start until all items it depends on are completed. The scheduler handles dependencies through the issue picker component.

The dependency checking process

When selecting the next item to work on, the picker begins by filtering out items with future estimated start dates. It then prioritizes items approaching their deadlines, giving them preference over items with more slack time. For each candidate, it checks whether all dependencies are satisfied by examining whether the dependent items have completion dates assigned. Only items that pass all these checks are returned as ready for work.

When an item has dependencies, the picker examines not just the item itself but also all its parent items in the hierarchy. If any parent has unsatisfied dependencies, the child item cannot proceed. This ensures that work respects the full dependency graph, not just immediate relationships.

Circular dependency detection

When no items can be scheduled despite having items in the backlog, the scheduler suspects circular dependencies. Consider a situation where item A depends on item B, and item B depends on item A. Neither can start because each waits for the other. This creates a deadlock that prevents progress.

The scheduler detects these cycles using a graph traversal algorithm. It builds a directed graph from the dependency relationships, then performs a depth-first traversal while tracking the current path. When the traversal encounters a node that already exists in the current path, it has found a cycle. The scheduler reports all detected cycles so that project managers can resolve them manually by removing or restructuring dependencies.

Deadline propagation

Items may have deadline constraints expressed as need-by dates. The scheduler propagates these constraints through the hierarchy to ensure that child items inherit the urgency of their parents.

When a parent item has a deadline, all its children effectively share that deadline. If a child also has its own deadline, the scheduler uses the earlier of the two dates. This ensures that the most urgent constraint always wins. The scheduler computes a latest schedule time for each item by working backwards from the deadline. Starting at the deadline date, it subtracts the assignee’s available hours week by week until it has accounted for the full effort required. The resulting date represents the latest point at which work must begin to meet the deadline. Items approaching their latest schedule time receive priority during selection. The picker identifies these time-critical items and places them at the front of the queue, ensuring that urgent work gets attention before less constrained items.

Work-in-progress management

The scheduler limits how many items each team member works on concurrently. This models the reality that context-switching between too many items reduces productivity. A team member juggling five items makes less progress than one focused on two.

Capacity limiting

At the start of simulation, the scheduler calculates the maximum number of in-flight items based on team size and a configured limit per person. If the current count of in-progress items exceeds this maximum, the scheduler moves the excess back to the backlog. Items are moved in their sorted order, preserving the priority established during preparation.

This limiting step may seem counterintuitive. Why would items already in progress be moved backwards? The answer lies in simulation accuracy. Real teams cannot effectively work on unlimited items simultaneously. By enforcing work-in-progress limits, the simulation produces more realistic completion dates.

Work tracking

Each team member maintains a work queue that tracks their currently assigned items and the remaining effort on each. The queue also knows whether the team member needs additional work based on the configured target workload.

When an item completes, it leaves the queue, creating capacity for new work. The scheduler detects this capacity during the daily cycle and attempts to fill it with appropriate items from the backlog.

Scheduling of parent items

Non-leaf items, those with children, do not receive direct scheduling. Instead, their schedules derive from their children through a bottom-up propagation process.

After all leaf items have been scheduled, the scheduler processes the hierarchy from leaves toward the root. For each parent item, it examines all children and sets the parent’s start date to the earliest child start date. Similarly, it sets the parent’s completion date to the latest child completion date.

This propagation continues up the hierarchy. A grandparent item derives its dates from its children, which themselves derived dates from their children. The result is a consistent schedule where every container accurately reflects the span of work it contains.

Skills and project access

The scheduler matches team members to items based on capabilities, ensuring that work goes to people qualified to perform it.

Skills matching

Items may require specific skills, indicated through labels attached to the item. A team member can only work on an item if they possess all required skills. Skills are defined as boolean flags in the team member’s profile, indicating whether they have each capability.

When the scheduler considers assigning an item to a team member, it extracts the skill requirements from the item’s labels and checks each against the team member’s skill set. If any required skill is missing, the assignment cannot proceed, and the scheduler looks for another team member or another item.

Project access

Similarly, items may belong to specific projects. Team members must have access to at least one of the item’s projects to work on it. This models organizational boundaries where not all team members can work on all projects, perhaps due to security requirements, contractual limitations, or simply team structure.

The access check works like the skills check. The scheduler extracts project labels from the item and verifies that the team member has at least one matching project in their access list.

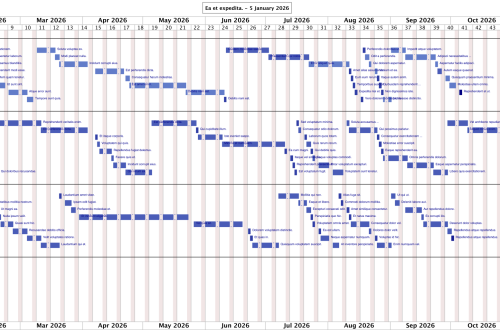

Simulation outputs

The scheduler produces several outputs that provide visibility into the simulation results.

The primary output is scheduled dates for all items. Each item receives a start date and completion date based on when the simulation determined work would occur.

The scheduler also produces a daily schedule log as a CSV file. This log captures metrics for each simulated day: available hours, backlog and in-progress counts, items started and completed, and team member headcount. Analyzing this log reveals patterns in how work flows through the system.

Work tracker data shows hours worked per team member per day, broken down by item. This output helps validate that the simulation distributed work reasonably across the team.

Finally, unallocated time records capacity that could not be assigned to any item. High unallocated time might indicate skill gaps, dependency bottlenecks, or other issues worth investigating.

Limitations

Circular dependencies prevent scheduling completion. While the scheduler detects and reports cycles, it cannot resolve them automatically. Human intervention is required to break the cycle by modifying dependencies.

Items requiring skills that no team member possesses remain unassigned. The scheduler cannot create capacity that does not exist. Such items stay in the backlog indefinitely, and the simulation may not complete.

Conclusion

The scheduler described in this article demonstrates how discrete-event simulation can model complex project scheduling scenarios. By advancing through time day by day and respecting real-world constraints like team availability, skills, and dependencies, it produces realistic completion date predictions.

The key insight is that scheduling is not a static calculation but a dynamic process where work flows through states based on resource availability and constraint satisfaction. Rather than seeking an optimal solution that would quickly become obsolete, the scheduler produces a probable forecast that can be regenerated as conditions change. This simulation approach naturally handles the complexity that makes traditional scheduling methods unreliable, while remaining practical for regular use throughout a project’s lifecycle.